Just received the latest, February 2007, issue of the

Virginia Seminary Journal. Pages 89-90 contain my review of John J. Collins,

Encounters with Biblical Theology (Fortress, 2005). The journal editor, Alix Dorr, has given me permission to post a copy of my review here on line. Enjoy:

Encounters with Biblical Theology.

By John J. Collins.

Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005.

Pp. x + 243. $22.00 (pb).

This volume is a collection of learned biblical essays, all touching on theological issues, published over three decades by John J. Collins. It should not be confused for a comprehensive or systematic work of biblical theology. The essays are clumped in sets under five headings: “Theoretical Issues,” “Topics in the Pentateuch,” “Wisdom and Biblical Theology,” “Apocalyptic Literature,” and “Christian Adaptations of Jewish Traditions.” Conspicuously absent is a separate section on Hebrew Prophecy. Throughout the essays, Collins’ writing is cautious, well-considered, and nuanced. This is a careful and erudite collection of knowledge, well documented through endnotes gathered at its conclusion.

The author is a senior scholar of Hebrew Bible, perhaps best known for his work on apocalyptic literature. He has now replaced Brevard S. Childs at Yale University, a sea change for the institution’s biblical department given Collins’ notorious disagreements with Childs’ mode of scholarship.

Collins’ polemical opposition to Childs’ neoorthodoxy and post-critical hermeneutics is conspicuous in this volume, where more than once he pits his own liberal modernism against Childs’ very different canonical sensibilities. Fighting on various other fronts, he also defends a resolutely historical-critical approach to the Bible against conservatives such as Donald Wiseman and Kenneth Kitchen and against postmodernists, such as Keith Whitelam.

Collins is deeply committed to the historical-critical method in studying Scripture, and understands biblical theology as a mere extension of that enterprise. He keeps his scholarly discourse public, rationalist, and historically anchored. His conclusions are almost entirely of a socio-historical nature, and require little or no spiritual sensitivity to appreciate.

Such an approach to the Bible has its merits. It opens up a safe space for ecumenical and interfaith conversation in which even pure secularists are comfortable. Properly insisting that religious thinkers engage evidence, mount arguments, and keep open minds, Collins appropriately reminds us that blind faith is no path to knowledge. These merits of Collins’ stance are laudable. If one is hoping for a biblical theology that is of service to the gospel and to the church, however, Collins’ work proves deficient.

For decades, Brevard Childs has pleaded with biblical theologians to attend to Scripture’s unique shaping, through which the Spirit has created and nurtured faith communities. If willing to do so, their exegesis would become relevant for ministry once again, stimulating and nourishing the active theological work and calling of church and synagogue. Dynamic interaction with the Bible’s inherent qualities as Scripture is the bread and butter of constructive theology, not interaction with the Bible’s hypothetical, pre-scriptural building blocks. Collins, unfortunately, discounts Childs’ plea.

“De-canonizing” the biblical texts and fastening historical-critical blinders on his readers, Collins short-circuits the prospects of his biblical theology. It cannot enliven the church’s contemporary theological task, because it lacks a means of engaging and illuminating the “Word of the Lord” to which the church attends. Collins’ biblical-theological work has nothing to say about any such “Word,” because the Scriptures for him lack a qualitative difference over against other ancient literature. The History of Religion approach is Collins’ ally, not the discipline of theology. Left unanswered is the question of why one should clump the Scriptures together with other ancient writings that lack the internal marks of a long vitality as the life-bread of the people of God!

For Collins, the biblical texts are of historical, not canonical, importance, and modern people must disavow much of their rhetoric and ideology. This is to understand the Bible in anthropological rather than theological terms. It is to take the Scriptures not as a witness to God’s truth but as “works of the [human] imagination, attempts to make sense of historical experience” (p. 32).

Collins is extremely reticent to speak directly about God’s activity in and purpose for history. Indeed, he requires the biblical theologian to bracket her ontological claims no matter how convicted of them she might be. Responsible academic criticism, he holds, does not have the resources to support such claims. This stance facilitates public discourse about biblical theology but at the expense of perpetuating the contemporary mutual isolation of biblical studies and dogmatics. Frankly, it also makes Collins sound a lot like a deist.

Collins’ hard-nosed historicism presupposes a philosophical naturalism. “Modern critical historiography requires that events be explained in terms of human causality,” he writes (p. 86). In one essay he describes the notion of divine intervention in history as a “mythological idiom” of the biblical text. In another, he approvingly quotes a statement by Rudolf Bultmann that Jesus’s miracles are incompatible with a modern conception of the world. Such a perspective on history that does not allow for transcendental causation is reductionistic and obviously stands at odds with traditional Christianity. In his labors to give the Scriptures objectivity over against later church tradition, Collins ends up subjecting them to the metaphysical commitments of Enlightenment rationalism.

In his essays, Collins follows the lead of Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923) in assuming that biblical texts must be interpreted to reflect the conditions and beliefs of their first, primitive settings. He writes, “The study of the Bible over the last two centuries has amply demonstrated that it is the record of a historic people, through the vicissitudes of its very particular history. The social message of the Bible, like everything else in it, is historically conditioned and relative” (p. 78). Collins does not come clean, however, about the crisis of unprecedented magnitude and depth that Troeltsch saw set in motion by the rise of this mode of approaching the Bible as conditioned and relative.

Troeltsch, in fact, argued that the historical-critical method had unleashed a crisis of historical relativism upon Christianity. This historical relativism constituted a “leaven” that would alter the faith forever. Eventually, it would even burst Christianity’s structures as they had hitherto been known. Unlike Troeltsch, and unlike many religious believers today, Collins apparently feels immune from the threats of this crisis.

Although a classic and influential document of religious communities, the biblical corpus lacks transcendent authority for Collins. Thus, he is free to reject those parts that stand in tension with the ethical commitments of contemporary humanism. In his essay “Faith without Works,” it becomes obvious that Genesis 22 is one such part of the Bible.

In this essay, Collins insists that Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac is morally reprehensible and beyond defense. Abraham, he writes, “cannot be invoked as a positive moral example for the modern world” (p. 58). I beg to differ! Far from reprehensible, Abraham’s shocking obedience to God in Genesis 22 flowed out of a riveted focus on the Lord’s wondrous goodness and provision.

Abraham obeyed God’s harsh command because he believed, despite all possible human calculation, that God would somehow not demand Isaac of him in the end or else would make things right in some other manner that only God could foresee—one that lay wholly outside the mundane, the everyday. The text practically shouts this truth.

When Isaac notices that he and his father lack a victim for their sacrifice, Abraham assures him, “God will provide for himself the lamb for the burnt offering, my son” (22:8). When Abraham chooses a name for Mount Moriah it is Yahweh-Yireh, “The Lord Provides,” “The Lord sees to it” (22:14). “Moriah” itself sounds like the Hebrew root for “provide” or “see to it.” That root appears five times in the chapter, which is unusually frequent. All this is no coincidence. The whole story of Genesis 22 revolves around how God wondrously provides for God’s people’s deepest needs, seeing to it they are met. This is the God whom Abraham found himself able to obey through faith.

In this short review, I have left the majority of essays in this volume untouched. They are all of high quality, however, and well worth reading for their historical-critical (if not theological) insights. The complete list of essays in the volume is as follows: “Is a Critical Biblical Theology Possible?” (pp. 11-23); “Biblical Theology and the History of Israelite Religion” (pp. 24-33); “The Politics of Biblical Interpretation” (pp. 34-44); “Faith without Works: Biblical Ethics and the Sacrifice of Isaac” (pp. 47-58); “The Development of the Exodus Tradition” (pp. 59-66); “The Exodus and Biblical Theology” (pp. 67-77); “The Biblical Vision of the Common Good” (pp. 78-88); “The Biblical Precedent for Natural Theology” (pp. 91-104); “Proverbial Wisdom and the Yahwist Vision” (pp. 105-16); “Natural Theology and Biblical Tradition: The Case of Hellenistic Judaism” (pp. 117-26); “Temporality and Politics in Jewish Apocalyptic Literature” (pp. 129-41); “The Book of Truth: Daniel as Reliable Witness to Past and Future in the United States of America,” with Adela Yarbro Collins (pp. 142-54); “The Legacy of Apocalypticism” (pp. 155-66); “Jesus and the Messiahs of Israel” (pp. 169-78); and “Jewish Monotheism and Christian Theology” (pp. 179-89). The volume includes a seven-page introduction by the author, an index of modern authors, and an index of Scripture and other ancient literature.

Stephen L. Cook

The Catherine N. McBurney Professor of Old Testament Language and Literature

Labels: book reviews

Under the category of neat links, there is a good looking model of Israel's wilderness tent

Under the category of neat links, there is a good looking model of Israel's wilderness tent

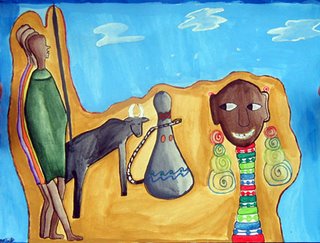

Here is an artist's reconstruction of Gen 31:19, the shrine of the ancestors in the house of Laban, Rachel's father.

Here is an artist's reconstruction of Gen 31:19, the shrine of the ancestors in the house of Laban, Rachel's father. While reading an excellent book on African Religions and Philosophy by John S. Mbiti, I was reminded that often we westerners mis-apprehend the practice of bride wealth (cf. 1 Sam 18:27). Mbiti writes, "Under no circumstances is this custom a form of 'payment,' as outsiders have so often mistakenly said. ...The two families are involved in a relationship which, among other things, demands an exchange of material and other gifts. This continues even long after the girl is married and has her own children." Further, Mbiti writes, "This marriage gift...is a token of gratitude on the part of the bridegroom's people. ...At her home the gift 'replaces' her, reminding the family that she will leave or has left and yet she is not dead. She is a valuable person."

While reading an excellent book on African Religions and Philosophy by John S. Mbiti, I was reminded that often we westerners mis-apprehend the practice of bride wealth (cf. 1 Sam 18:27). Mbiti writes, "Under no circumstances is this custom a form of 'payment,' as outsiders have so often mistakenly said. ...The two families are involved in a relationship which, among other things, demands an exchange of material and other gifts. This continues even long after the girl is married and has her own children." Further, Mbiti writes, "This marriage gift...is a token of gratitude on the part of the bridegroom's people. ...At her home the gift 'replaces' her, reminding the family that she will leave or has left and yet she is not dead. She is a valuable person."